Self-Efficacy, simply defined, is the capacity to cope. This makes it an important life skill which contributes to how individuals manage changes in health over the course of their lifespan. Self-efficacy provides a psychological resilience, which, along with physical resilience, has the potential to allow older adults to change the trajectory of aging and the development of frailty.

Dr. Albert Bandura, the founding scientist in the field, has said, “Belief in one’s efficacy to exercise control is a common pathway through which psychosocial influences affect health functioning (Bandura, 2004).”

There is to date minimal research on direct relationships between self-efficacy and physical frailty as defined by the Fried Frail Scale. However, there is a growing body of literature on self-efficacy and interventions to improve health outcomes among those with either multi-morbidity or functional decline (Gill et al., 202),(McPhee et al., 2016 ). Recognizing the impact of self-efficacy on the ability of interventions to affect health-related changes highlights the need for frailty research to incorporate this important dimension.

Higher self-efficacy has an inverse relationship with frailty, and with physical function among those who are frail. Stretton and colleagues found that a high level of self-efficacy was the single best predictor of physical functioning in frail older adults (measured using a clinician rapid screening) in older adults needing to engage in fall prevention strategies (n=243) (Stretton et al., 2006). Hladek and colleagues (2019) found a cross-sectional association between high coping self-efficacy and lower odds of pre-frailty/frailty (using the FRAIL Scale) in 146 older adults with chronic disease (Hladek et al., 2019). Qin and colleagues (2020) also observed a relationship between higher general self-efficacy and lower likelihood of frailty (measured using a deficit accumulation index) on life satisfaction in a Chinese cohort of older adults (n=7070) (Qin et al., 2020). These findings are associations and therefore it is not known whether low self-efficacy is causing frailty or vice versa. For example, it may be that the experience of frailty leads to a loss of self-efficacy. Hoogendijk and colleagues (2014) showed that higher general self-efficacy buffered against functional decline in 1,665 Dutch physically frail older adults (Hoogendijk et al., 2014). Still, more prospective research and intervention trials are needed to answer these questions on a broader population basis.

Biological Feedback with Self-efficacy:

There is a plausible mechanism by which low or declining self-efficacy may be causal in a physical decline. Bandura and colleagues conducted a series of experiments to evaluate the hypothesis that self-efficacy mediates the relationship between environmental stress and physiological feedback from the stress response. His work with a small experimental group (n=20) of subjects with arachnophobia (extreme fear of spiders) showed clear attenuation of catecholamine secretion and heart rate in the presence of high coping self-efficacy when confronted with a spider, meaning lower levels of activation of the sympathetic nervous and hypothalamic-pituitary adrenal axis (Bandura et al., 1985), (Bandura et al., 1988). Pro-inflammatory changes in immune markers like T-cell and B-cell quantities and Interleukin-2, a pro-inflammatory cytokine, were also observed (Wiedenfeld et al.,1990). These results suggest that if a person evaluates a stressor as being manageable, because they have high self-efficacy, there will be less of a physical stress response when they are confronted by that stressor, and thus better health–since stress responses create wear and tear on the body.

One recent study of Alzheimer’s caregivers showed self-efficacy moderates the relationship between psychological stress and an inflammatory cytokine (Interleukin-6) in a healthy older adult population (Mausbach et al, 2011). When self-efficacy was low, caregiver’s reported sense of stress/overload was significantly related to IL-6 (β = 0.53). When self-efficacy was high, overload was not significantly related to IL-6 (β = -0.17). This study reveals a potential protective effect of self-efficacy on inflammatory processes. Further cross-sectional research has also shown associations between high coping self-efficacy and lower inflammatory markers in older adults with chronic disease (Hladek et al., 2019).

Research on self-efficacy confirms that it significantly influences the ability of individuals to affect behavior change across a broad range of health conditions and outcomes. Thus, understanding the role of self-efficacy in health is important in the study of frailty because the most studied interventions for frailty typically require patient participation–for example in diet and exercise programs–where commitment requires higher levels of self-efficacy.

Improving Self-Efficacy:

Interventions are available to improve self-efficacy. Dr. Kate Lorig and colleagues at Stanford University developed the Chronic Disease Self-Management Program (CDSMP), a 6-week participatory program led by an individual with the targeted chronic disease and one healthcare professional. Content focuses on process knowledge (like problem-solving, decision-making, brainstorming, and action planning), breaking symptom cycles (like pain, frustration, isolation, and fatigue), communication techniques, and simple content messages around exercise, nutrition, and the appropriate use and evaluation of medication. This program has been shown to increase self-efficacy for individuals with chronic disease and simultaneously increase their positive health behavior and decrease disease metrics as well as healthcare utilization over a two-year period (Lorig et al., 2001). Randomized control trials have demonstrated benefits include decreasing blood glucose levels in diabetic patients over time (Trief et al, 2009Zulman et al., 2012), better weight loss (Hays et al., 2014), and decreased arthritis pain in another small RCT (Lorig et al., 1989).

Incorporating self-efficacy into frailty research requires finding ways to measure it. Self-efficacy is specific to specific domains–it may be high for exercise but low for technology usage. Therefore, researchers need to devise methods to capture the breadth and depth of that particular domain. It is not simply a marker of knowing what to do. For example, the Self-Efficacy For Chronic Disease Management Scale (Lorig et al., 2001) asks 6 questions about managing the symptom burden of disease, such as fatigue, physical discomfort, and emotional distress as well as performing actions to manage a health condition (Lorig et al., 2015).

Self-Efficacy and Social Cognitive Theory:

Social cognitive theory seeks to understand how the interactions between personal attributes, behavior and environment inform how people think and act. In the context of health, social cognitive theory can be used to understand how personal change and behavior modification can be leveraged to help prevent disease progression and achieve increased health and wellness. There is a core set of determinants that contribute to the ability to undertake personal changes for health: knowledge, perceived self-efficacy, outcome expectations, health goals, and perceived facilitators and impediments (Bandura., 2004). Of these core determinants, perceived self-efficacy is central, guiding and influencing the other determinants.

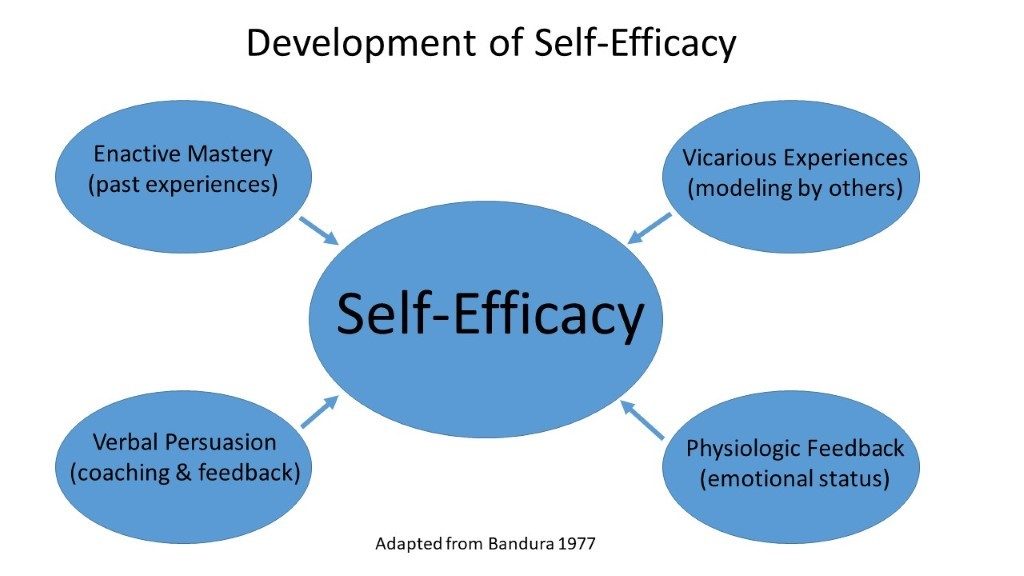

Self-efficacy is thought to develop through four sources (Bandura, 1997):

(1) Enactive mastery experience involves prior success in an area of life that offers authentic personalized evidence that the same results can be achieved again. For example, after practicing how to perform blood glucose monitoring with a nurse, an individual will have confidence that they can do it at home, and thus will be more likely to follow through with that important engagement in their health.

(2) Vicarious experience involves observation, learning and comparison to others in one’s social network to grow in confidence in the ability to achieve a good outcome. This source of self-efficacy is greatly influenced by the group chosen for social comparison. An individual who has friends who have navigated weight loss by implementing an exercise plan may be able to follow that behavior and start exercising themselves.

(3) Verbal persuasion is the expression of faith in another’s capabilities. It can augment the adoption of change if the verbal persuasion is within realistic bounds. Providers may have patients return to clinic at short intervals to optimize the impact of persuasion in helping a patient establish better habits around their diabetes management including carbohydrate counting and taking daily insulin injections.

(4) Physiologic feedback involves physical and emotional responses to the environment. These responses are the result of a feedback loop between perceived stress and the perceived self-efficacy capacities to buffer that stressor. Physical and emotional responses to life stressors literally affect how people feel in their bodies. Mood states also interact with people’s judgments of their personal efficacy. Likewise, physical symptoms of fatigue or aches and pains can influence efficacy. People routinely recognize such physical feelings, for example from excess adrenaline and cortisol, as vulnerability and consequently feel less confident in their ability to cope with a particular situation. As the individual works to resolve or cope with the stress, these physical changes improve and efficacy also improves in a positive cycle.

These four sources of self-efficacy development are consciously and unconsciously collected, integrated, weighted and reflected into judgments by individuals to contribute to an overall self-efficacy as well as their specific sense of competence in any given life domain (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Development of Self-Efficacy